Do We Understand AI?

Like, what does it even mean to *know* anything, man?

I recently came across an ‘intriguing’ thread by @dystopiabreaker.

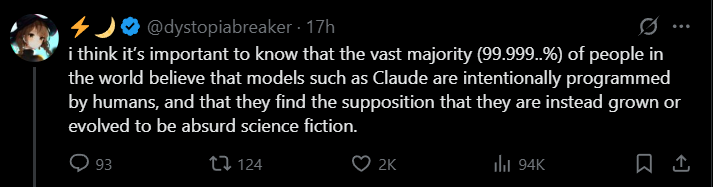

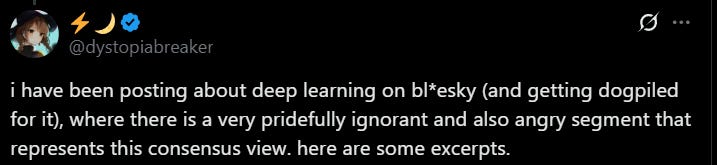

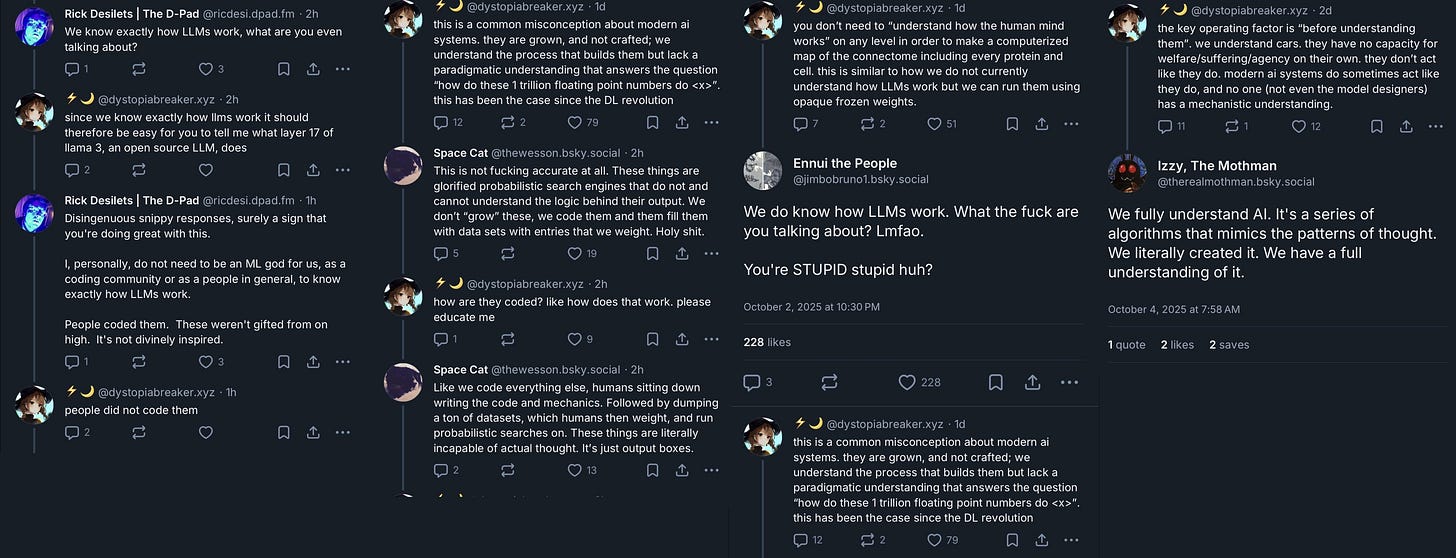

They had apparently been embroiled in a harsh series of arguments on Bluesky, and unfortunately lost the like-ratio war there. Rather than accept defeat, they restarted the discussion on the more favorable turf of “X,” or, the artist formerly known as Twitter:

Bringing this argument to Twitter was a good move, as I could not find any disagreement among any of the dozens of TPOT blue check accounts that replied or quote-retweeted this thread. Instead, I found predictions of a “permanent underclass” for those who are unjustly convinced of the programmed nature of AI, and jokes about individuals on Bluesky being so self-assuredly confident about a position so incorrect.

These discussions struck me as quite odd. One less charitable interpretation of ⚡️🌙’s words is that AI models are so unknowable as to be magic (this is certainly how the Bluesky repliers describe their views) and yet a lot of people on Twitter seem to have a great deal of knowledge on these models. So much so that they can hold this knowledge over others’ heads as a sense of superiority.

But if no one understands AI, then how can we create a “permanent underclass” out of those who don’t? Besides an imagined future where AGI makes humanity itself an underclass, that is.

The simple answer is that no one actually believes that AI is entirely unknowable, or at least, no one relevant. Actually, this entire argument is just a story of two sides arguing past one another. Not that the two don’t have competing values and genuine viewpoints, no; this confused argument is actually motivated by those values, and it explains why they might never see eye to eye, even after this discrepancy is described.

Regardless, I will try my best. Lost causes are still causes, and I like the sound of my own keyboard.

Here are some facts that both sides would agree with: humans are capable of understanding what the term “neural network” means. People are capable of taking university classes that are allegedly about artificial intelligence and machine learning. There are engineers employed at companies like OpenAI and Anthropic who perform work on artificial intelligence, and who received degrees in related fields.

Does that mean that they understand AI?

I’m not sure I’ve elucidated the question any further, but we’ve made some progress. Certainly those who have taken such courses in college have more of an understanding of AI than a layperson, and those who work at OpenAI have a substantially deeper understanding of ChatGPT than even those who take a generic course. Yet a researcher at Anthropic said about such models, “we just don’t understand what’s going on here.” How?

That researcher is Sam Bowman, who was interviewed in an article from a few years ago on this same topic. Truthfully it could do most of the job as my own, but I’ll repeat its central points. As Sam says immediately afterwards, “we built it, we trained it, but we don’t know what it’s doing.” This is the core thread of distinction in our argument, and it’s one that neither side in the Bluesky or Twitter threads did much to pull at.

People can describe the systems that are running on the computer in a general sense; they can explain the math, they can point out the meaning of individual terms, and they can do work to actually implement this all in a way that can actually be run. These are the things we do know, or at least, those of us with experience. The parts we don’t know are the ways that the model operates within that system.

One point of heckling on Twitter was that many of the AI skeptics would admit to not understanding how it works at the implementation level, but would nonetheless claim that it is possible to know. It was bemoaned that they would make this case while not understanding it themselves.

At the very least, this criticism calls into question who the “we” is in our discussion. Perhaps the systems are understandable, but only to the very smartest engineer in the field. So, for the sake of our discussion and an analogy, let us pretend that you, the reader, are this engineer.

Picture yourself with no access to a working computer, merely a full understanding of how a computer functions and the underlying principles. If you were to be given a full description of a basic neural network implementation, a list of weights, and an input, would you be able to work out the output by hand? If you’ve ever taken a machine learning class you’ve likely done this exercise, and it’s clear that even as the network grows more and more complicated, it would remain technically possible to do this. Exponentially longer, yes, perhaps to the point of taking your entire natural life to complete and being unavoidably rife with human error, but one person would still be capable of processing the entire network fully, one step at a time.

In doing so, you would have taken the role of the AI and rendered an output exactly as the model would (barring errors). So, could we say that you understood the AI? Clearly you had a deep enough appreciation for its inner workings as to perfectly recreate it, to the point that no one on the outside would be able to look at the outputs alone and differentiate them. It’s not clear that it’s the same as understanding the model, though.

The distinction reminds me of the “Chinese room” analogy1. The concept is similar to the one I created, with a man in a room being given input strings of Chinese symbols. He then follows a book with a list of instructions on what to do for each symbol, creating an output. The key point is that the man does not speak Chinese, and so has no idea what the symbols mean, or even the importance of the instructions.

This is not likely to be a new topic for those experienced in AI, and many are familiar with its use in explaining that AI does not rationalize or ‘think’ when creating output. Indeed, it could be considered ‘proof’ that there is no consciousness in an AI system at all. I’m not particularly interested in those discussions here, though; instead, it is an interesting comparison to you, who went through and implemented the neural network by hand. Much like the man in the room, could it be said that you understood the AI of the neural network?

Maybe or maybe not. ‘You,’ in implementing the neural network as I described, don’t only know the steps to do so, but also the general motivation for them. You know how ‘backpropagation’ works, and what determines the choice of ‘activation function’, including fears of ‘linearization.’ You likely know the difference between a ‘CNN’ and a ‘RNN’ and why to use each, or even how to implement these in various languages. The man in the Chinese room doesn’t know anything about his steps beyond what to do at each step.

But still, in this hypothetical, you do not have perfect knowledge. You understand all the principles of the implementation, but if you were asked how the output might change for a specific random input, you would not necessarily have an intuition for it. You might have to trace through the various weights to see how that change would propagate, and by the end you might’ve had to calculate the entire output anyways. So for all your knowledge, you are still irrevocably bound by these arcane steps.

Perhaps the best term here is ‘chaotic.’ Much like the weather or particle systems, you can fully comprehend every single small mechanism behind a situation and still have no picture of what the output might look like for a specific input. As they say, even a small initial change, like a butterfly flapping its wings, leads to a dramatic shift in the final result, one that no one could ever predict without working it all out. If that’s the case, then it’s not clear how a holistic understanding of the system could exist at all. All you can ever understand is its individual parts, the system itself being invisible.

AI systems seem to have some of these elements of chaos, at least to me.

Every week a new comedic ChatGPT response is discovered, and no doubt the engineers at OpenAI respond to each and every one of these with a detailed investigation into the steps that the model took in generating the poor results. Often times, those who come across these hilarious responses attempt to recreate them locally, only to find it answering unexpectedly normally. The problem is that a lot of these issues simply do not replicate well. Even small adjustments like a difference in punctuation can change the failure state. Thus engineers are faced with the daunting task of not only identifying what series of mistakes on the model’s part caused the issue but also how to adjust the infrastructure of the model such that every instance of that problem is fixed.

Software engineers will recognize this as ‘debugging,’ and it is not entirely arcane. Many bugs in traditional software are difficult to reproduce, and many more are difficult to fix across all cases.

The main difference in my view is that the bug does not emerge from the program implementing the LLM acting improperly, but rather from the weights, themselves a sort of input from the perspective of the program, performing insufficiently. Since, unlike code, there were no humans involved in directly setting these weights, there is also no guarantee that any analysis could be performed on the exact purpose of these weights, and so determining which to change and how is at best as easy as decompiling machine code.

Instead, the easier way to fix these flaws is by blasting it with new training. For a disengaged teacher, it is probably easier to continue assigning failing grades to a student in hopes they eventually learn to stop giving bad answers than it is to find the root of their misunderstanding. If this is the approach used by the people being paid such ridiculous sums of money on this topic, it seems quite rational to say that no one really, truly, genuinely knows what’s going on.

Of course, this isn’t true for every issue - in fact, as I was writing this article, I found a good discussion of just why the seahorse emoji question causes so many LLMs to freak out. In a lot of cases, it is actually possible to ‘debug’ the issues. It takes a lot of work, but that’s outside the point. Maybe if we could have people combing through the predicted tokens at every step of every flawed ChatGPT answer, we can eventually develop a perfect understanding of the model, albeit spread across the minds of many engineers. Or perhaps no amount of analysis could ever result in comprehension of the entire system, its details complex as they are.

Many ‘artificial intelligence’ enthusiasts loathe that they’ve become associated with the term, believing that it has poisoned the well with people’s expectations that these models necessarily behave as the human mind would. Skeptics believe the same, though motivated more by cynicism than optimism. Even still, comparing it to our own brain was one more metaphor I kept coming back to as I turned that Twitter thread over in my head again and again.

‘Neural’ networks aren’t just a buzzword; they were explicitly designed to represent the human neural system, and clearly got close enough to work. If people can describe complex interactions within models like ChatGPT — ones that have only existed for a few years — to diagnose their flaws, then surely the several thousands of years of musing about how humans think and a century of medical analysis might have given us an even greater understanding of our own minds.

Physically, yes, it has. You can find exceptionally detailed schematics of the human neuron alongside paragraphs and paragraphs of explanations on the chemistry behind them, and on the biology of how the cells are created, grow, and link up. We have nearly fully mapped all of the neurons in the brain and where they connect to the rest of the body. We have developed detailed simulations of sections of brain that strive to recreate human behavior out of the digital, such as in the Brain Simulation Platform.

With all that in mind, one might imagine we know, say, what part of the brain does what. Certainly in the abstract we have been taught about the general roles of each region, and are likely to be correct on most of those, but even now there are questions about this understanding.

Most parts of the brain had their role first identified via gruesome injury; someone would suffer damage there, and then be unable to perform some human function, and thus the two must be related. Broca’s area, thought to be responsible for composing grammatical speech, was so named after Paul Pierre Broca. His identification of multiple patients experiencing similar speech impairment alongside physical damage to this area caused him to draw the connection. fMRI scans have also found heightened activity in the area while speaking, and so no one can doubt the connection.

Yet there have been many cases of tumors being removed from the area, destroying it nearly entirely, and yet leaving the victim with full speech abilities. There are various explanations, such as neuroplasticity, which is the idea that the brain can reassign responsibilities to other areas. A tumor is likely to allow time for this to occur, while blunt force trauma is not. Others take it as a sign that the area is not so critical to speech processing as has been thought.

What is the takeaway here? Well, we can see that there is a lot of ambiguity in understanding the purpose of various regions of the brain, and we are very, very far from being able to fully simulate the human mind or identify the exact purpose of specific neurons. Despite this, we still say we can understand the general functioning of the brain. We know the chemistry around neurons and we have created detailed and complex mappings of them. Neuroscience has led to numerous specific and useful advances that are being used in surgeries at this moment.

In other words, we understand the physical implementation of the mind without having fully realized vision of how the mind actually functions. This is the best description we could give to AI, too. We can build the neural networks, train them, and even analyze all of their weights; we can run them on GPUs custom built for them; we can have heated arguments on node count and deep learning techniques and all sorts of other technical details that the average American would hear as technobabble. But there’s a reason that Sam Bowman and just about every software engineer I’ve ever heard describes LLMs as black boxes. We understand the AI, but we don’t understand what is going on inside of it.

This whole exercise so far has been a bit redundant. Two sides arguing at each other, each winning on a different platform. None are likely to read this article, and somehow fewer are likely to have their mind opened by my rephrasing of the issue. When the issues at stake are values, not words, then my critique and discussion of the words will have little bearing on the topic.

At the same time, I can’t help but hope it matters somehow. Maybe if each side really did know what the other meant, it would lead to more productive arguments. Perhaps some values would shift as a result. Perhaps I am being overly cynical, and people’s beliefs really are predicated on the nature of this argument along the lines that I’ve drawn. At the very least I can feel like I, personally, have carved out a winning ‘third way’ in this incredibly annoying social media debate, which is one of the few pleasures left to us in this addled world.

Notably developed by John Searle, who passed away only three weeks ago and whose later years were defined by sexual assault allegations.